Works in Indian ink, Indian ink wash, gouache, marker & pencil

JONATHAN SWIFT (& H. G. WELLS)

In his Joyce biography Ellmann remarks that H. G. Wells, in a generally favourable review of Portrait Of An Artist, likened Joyce to Swift when he said that Joyce too had ‘a cloacal obsession’. Joyce in turn would later remark to Frank Budgen that ‘Why, it’s Wells’s countrymen who build water-closets wherever they go,’ ‘a charge he would renew in Ulysses,’ writes Ellmann, adding that, privately, Joyce ‘said to a friend, “How right Wells was!”’

Swift’s scatological obsessions are infamous, and scholarship—psychoanalytic and otherwise—has not shied away from dwelling on them, almost as much as Swift himself did. It is possible that he authored an essay called ‘The Benefit of Farting Explain’d’ (1722) and another treatise on human excrement under the pen name ‘Dr Shit’. But this has never been verified. Certainly Swift had trouble reconciling humanity’s creative and intellectual grandeur with its ‘baser’ animal nature; just as he could not keep separate his admiration for female beauty and his attraction to individual women from the fact that, as he writes in his poem ‘The Lady’s Dressing Room’, ‘Oh! Celia, Celia, Celia shits!’.

And yet Swift is, beyond doubt, one of the greatest writers and satirists in the English language, an artist whom Joyce greatly admired, not least for his readiness to speak truth to power (see A Tale of a Tub; A Modest Proposal; and ‘Drapier’s Letters’).

In this illustration (and in keeping with the best possible taste), Swift poses ‘cheekily’ astride a Victorian cistern whilst observing Joyce hungrily consume his work. From the cistern’s unconnected waste pipe issue harmless white clouds of inceptive Swiftian gas which rise above him to form inchoate thought bubbles—possibly mingling with Joyce’s own cigarette smoke—soon to assume a form less intellectually amorphous. Because, like everyone else, Swift’s noble thoughts and base obsessions are inextricably linked.

Famously, Bloom’s first appearance in Ulysses (Part II, Calypso) includes a routine morning visit to the ‘jakes’, and throughout the entire book Joyce does not hold back from detailing many of his characters’ thoughts and bodily processes concurrently—one of the many reasons the book was branded ‘obscene filth’ and banned. Bloom’s movements, in every sense, provide a welcome relief to Stephen’s in the preceding episode (Proteus) and the latter’s at times relatively abstract, even slightly ‘constipated’ over-analysis of himself, his life and his surroundings. His eventual encounter with Bloom and their shared drunken experiences, bring Stephen the much-needed ‘roughage’ required to restore him to human wholeness and good health.

Many Victorian cisterns had decorative—commonly, floral—patterns on their sides, and the stylised shamrock pattern on Swift’s cistern is taken from Augustus Pugin’s wallpaper design ‘Rose Thistle and Shamrock’.

From high on his throne, Swift dismisses a pontificating Wells with an indifferent flick of his finger.

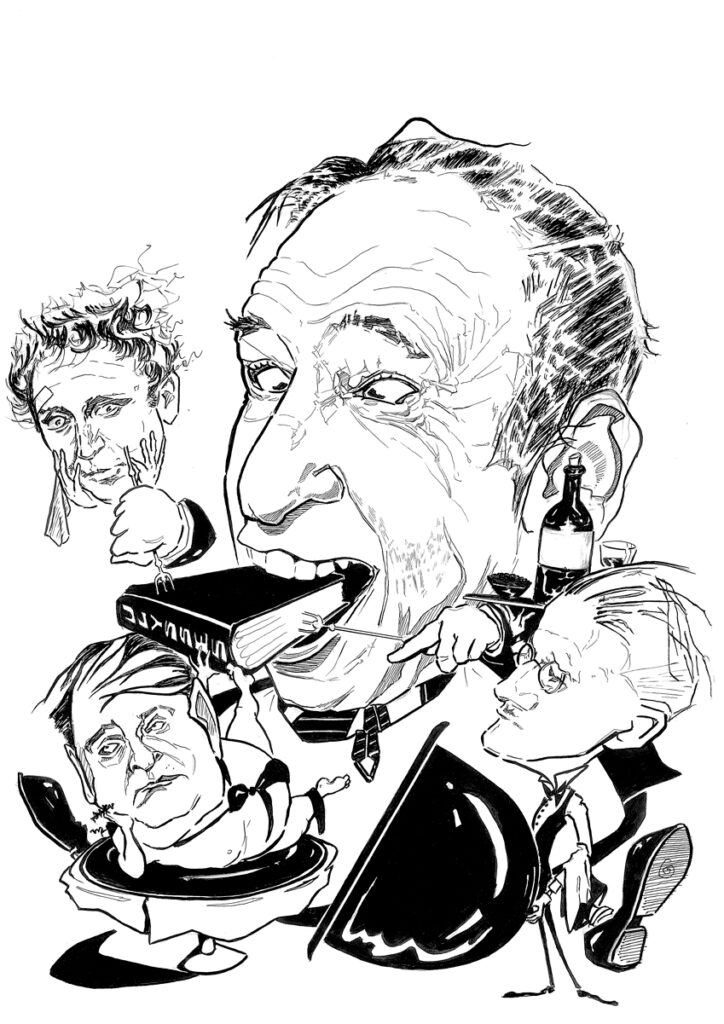

MEL BROOKS (ZERO MOSTEL & GENE WILDER)

Brooks is shown devouring a copy of Ulysses—a seemingly unlikely source of energy and stimulation behind his film The Producers, one of the greatest cinematic comedies ever made (pace the otherwise spot-on New Yorker critic Pauline Kael who dismissed it as little more than a tedious gag-fest; a verdict with which later generations might concur, given how dated some of the jokes have become).

One of the two heroes of the film is Leo Bloom—played by Gene Wilder—named for his Joycean counterpart, and in at least one draft screenplay, in a scene set in Max Bialystock’s office, a wall calendar shows the date to be the 16th of June after an exasperated Wilder wails ‘when will it be Bloom’s Day?’ (…dropped from the film). Wilder’s character does possess key ‘Bloomish’ qualities as found in Ulysses: he is highly sensitive and thoughtful; far cleverer than he might at first appear to many; and he tends naturally to forgive and look with a somewhat charitable eye on others’ flaws (consider the ironic courtroom speech made by Wilder near the end of the film, begging forgiveness from the judge—not so much for Bloom but for his fellow producer and partner in crime Max Bialystock).

For Brooks, Bloom is the perfect Everyman—a somewhat nebbishy but kind accountant (Joyce’s Bloom is an ad canvaser). But Brooks was cagily disingenuous when pressed on how much he got from Joyce’s novel, possibly not wishing to appear too ‘highbrow’, given how absurd, rollicking and even childish so much of his comedy can be. According to a Vanity fair article on the making of the movie (6 January 2004): ’Next came the hero’s name: Leo Bloom. Brooks borrowed it from James Joyce’s epic novel Ulysses. “I don’t know what it meant to James Joyce,’ Brooks told the theatre critic Kenneth Tynan in a 1978 interview for The New Yorker, “but to me Leo Bloom always meant a vulnerable Jew with curly hair.”’

In Brook’s 1967 production, Max Bialystock is played by Zero Mostel, who years before had performed on Broadway in the play Ulysses in Nighttown (based on the Circe episode), in the role of Leopold Bloom.

Brooks loves his food—his late wife Anne Bancroft thought he cooked the perfect omelette—and he still regularly meets with his old friend Carl Reiner to eat, drink and reminisce.

In this illustration, Joyce as waiter lifts the dinner cloche (a Bloomian bowler) under which a well-prepared Mostel has been keeping. Mostel has been largely divested of his theatrical Bloom costume (his right hand still clutches his prop moustache and Bloom’s black necktie serves to preserve his modesty) in preparation for his new role under Brooks’s direction. A nervous and neurotic Wilder looks on with fascinated horror and anticipation. Mostel resignedly helps Brooks to consume and savour his meal so they can all get on with it … creating a comedy masterwork.

The drawing style and composition of this piece is a deliberate homage to the artwork and artists of the film posters of the 60s and 70s (sadly rarely commissioned these days) which I loved as a child and teenager and which taught me more about drawing and composition than some of my art teachers ever did.

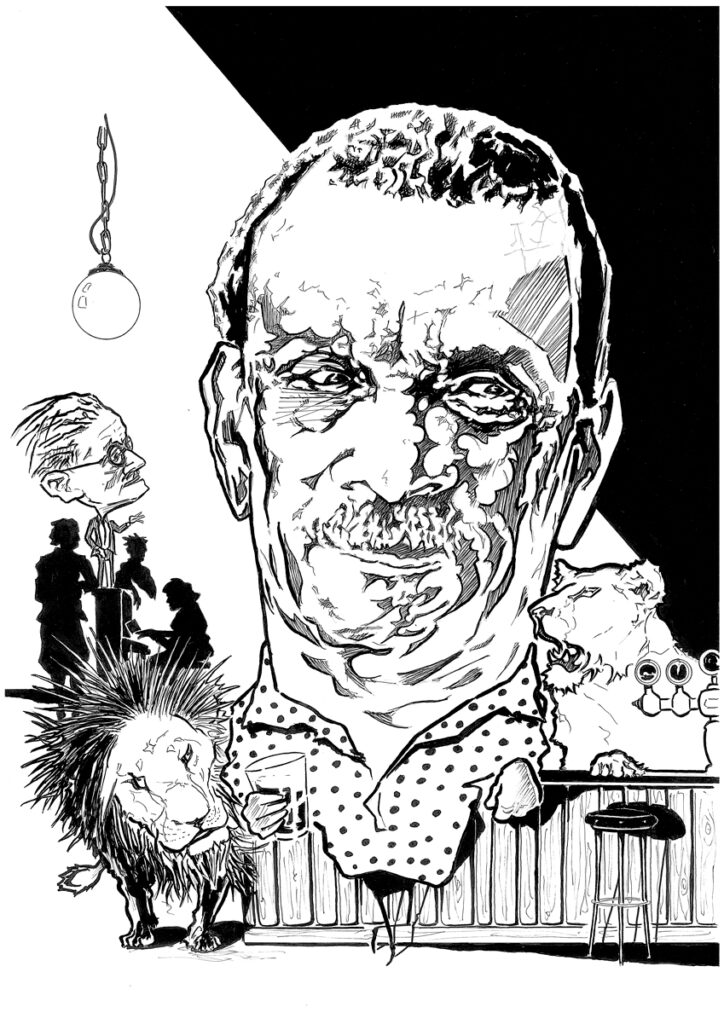

GEORGE MOORE

Joyce and the much older Moore’s relationship was scratchy and arm’s-length at best. Moore’s short novel Confessions of a Young Man (1888), preceded Joyce’s Portrait by almost thirty years, and because Moore considered his book better, he thought Joyce’s novel pointless. Joyce’s opinion of Moore was hardly high either, but Moore’s novel and the many others he published courted controversy due to their frank portrayal of sex, prostitution and the so-called ‘lower’ orders and struggling, starving artist-types—in keeping with French ‘Naturalism’—hitherto portrayed (most notably in opera) as Romantic heroes and heroines regarded with a patronising eye askance and a ‘there but for the grace of God go we’ attitude. Whether or not Joyce ever cared to admit it (unlikely) Moore and others had helped to sufficiently stir things so that when the younger Joyce appeared on the scene, this sort of literary controversy was hardly new.

But Joyce was the greater artist by far and he knew it. He maintained a cordial veneer of respect towards Moore, which was forever on the verge of cracking up. When Moore returned to Ireland from the Continent in 1900 to help the Gaelic League, a still-adolescent Joyce wrote: ‘Mr Moore’s impulse has no relation to the plane of art.’ The wreath sent by Joyce on news of Moore’s death in 1933 included the one, less-than-plangent line: ‘To George Moore from James Joyce.’

As noted, Moore’s young adult years were spent on the Continent, notably in Paris, where he trained and failed as a painter. In this picture Moore attempts a portrait of a cocky Joyce, who turns his gaze away from Moore whilst crotch-clutching the obligatory floral, life model prop; he aims Stephen Dedalus’s ashplant directly at a befuddled Moore’s jugular—an empty wine bottle serving as potential ammunition. The failed painter Moore can only manage to portray Bloom’s bowler proudly sported by an otherwise nude (but wholly confident) Joyce, without so much as a clue as to what the image would come to represent in modernist art and literature—easily facing down its true iconic competition in the form of René Magritte’s Son of Man painting, and Agatha Christie’s Belgian detective Hercule Poirot’s homburg, which is a variation of the bowler.

MARGARET ATWOOD

Her outfit and pose inspired by Penelope’s in Angelica Kauffman’s eponymous painting (1764) of Odysseus’s long-suffering wife ‘at her loom’, Margaret Atwood reposes with a smile, not a disconsolate pout, because her Odysseus at long last has returned. Joyce, in a get-up also inspired by Kauffman’s many portrayals of Odysseus, kneels next to Margaret and rests his shield on a bust of blind Homer. The blade of his sword tapers to end in the nib of a writing pen. Under his left arm he carries a copy of Atwood’s novel Penelopiad, a radical retelling of the myth of Odysseus’s wife.

As Atwood writes in her introduction to the novel: ‘Homer’s Odyssey is not the only version of the story. Mythic material was originally oral, and also local…I have drawn on material other than the Odyssey, especially for the details of Penelope’s parentage, her early life and marriage, and the scandalous rumours circulating about her. I’ve chosen to give the telling of the story to Penelope and to the twelve hanged maids…The story as told in the Odyssey doesn’t hold water: there are too many inconsistencies. I’ve always been haunted by the hanged maids; and, in The Penelopiad, so is Penelope herself.’

On 15 June 2018 (one day before Bloomsday) Margaret Atwood accepted a Ulysses Medal at a University College Dublin event ‘Imagining Home’, organised by the College of Arts and Humanities. (James Joyce graduated from UCD in 1902.) UCD reported that Atwood said ‘it could not be “overestimated” how important the Irish writer’s depiction of fictional hero Leopold Bloom in Ulysses was to developing modern literature. “Leopold was not exactly Love’s young dream…[but] serious novelists in the 20th century usually opted for Bloom while poor Heathcliff has been relegated to the gothic romance. Ulysses moved the needle in the direction of warts, that’s why it was so widely banned…because it drew attention to the essential human,” she added.’

In this drawing I have tried to give Atwood a timeless, other-worldly, even mythical mien, in keeping with the woman she portrays, and to whom Joyce does great (and equally idiosyncratic) justice in Ulysses. On the table behind her stands a black-figured neck-amphora (British Museum number 1866,0805.3). The vase design shows the blinding of Polyphemos: ‘Odysseus and two companions advance to right, bearded, with swords and short chitons…holding aloft the pine-tree which they thrust into the eye of Polyphemos; Odysseus’s left foot is raised against his chest.’

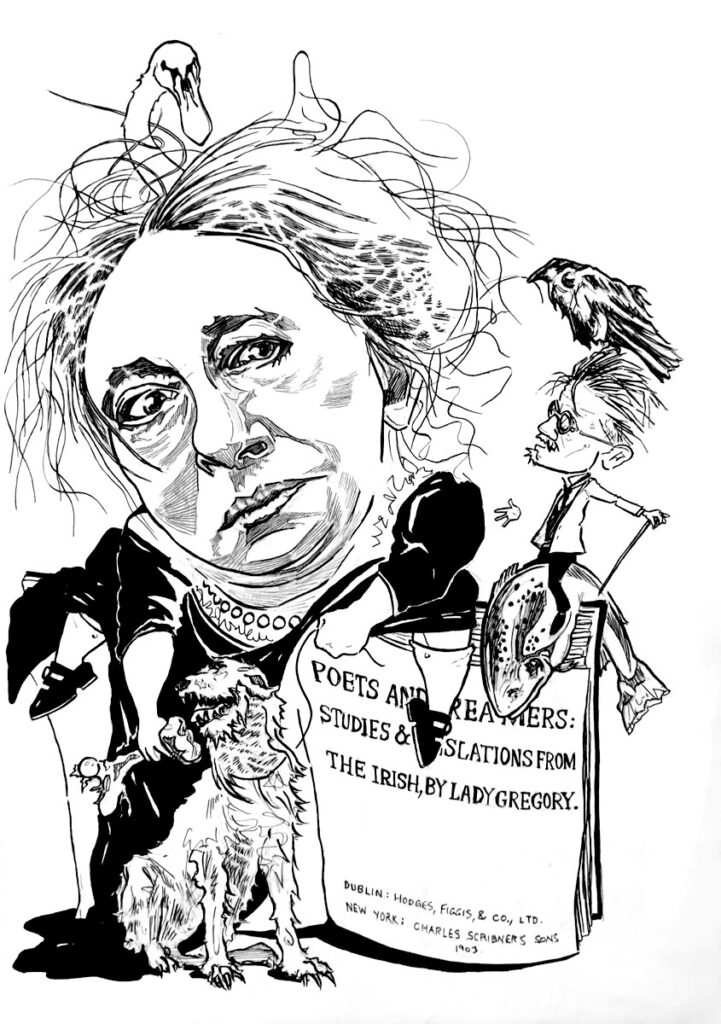

LADY AUGUSTA GREGORY

Irish playwright and folklorist, Gregory was a close literary collaborator with W. B. Yeats and Edward Martyn, with whom she co-founded the Irish Literary Theatre and the Abbey. A very young Joyce was keen to enlist her support, both financial and social, to advance his burgeoning career, and he befriended her by writing her plaintive letters and pursuing other established writers and intellectuals in her circle, notably Yeats and George Russell. Lady Gregory always lent him a sympathetic ear (though not much in the way of cold hard cash), but this didn’t inhibit Joyce from writing typically acerbic reviews of her work. When he was sent Gregory’s Poets and Dreamers to review (writes Gordon Bowker in his biography of Joyce), it ‘prompted Joyce to resume his attack on the rabblement. Having been befriended by the author did not inhibit the fearless critic. The folktales in this collection, recounted by old people in the west, he wrote, were often the product of feeble, meandering and sleepy minds, and were not as ironically and delicately treated by her ladyship as they had been by Yeats in The Celtic Twilight. Although unkind to Gregory’s book, he was not dismissive of Irish folklore and legend, as his final many-layered novel, itself a modern meandering Irish legend, would demonstrate’.

A somewhat flustered Gregory is pictured here attempting to defend her work from a hectoring Joyce who has easily scaled the ramparts of her book. She is accompanied by a few of the animals found in the Irish folk legends she, Yeats and other scholars of the day recount and analyse. Gregory offers a bone to the hound of Cullen, from which the great warrior Cú Chulainn gets his name for slaying the beast.

The swan nesting in her hair is one of the mythological Sea Lord Lir’s children, turned into the fowl along with its siblings by Lir’s second wife, Aoife (sister of his first late wife) who did not like them; the swan spell would last until they heard a Christian bell but it wasn’t until after a rather long 900 years that St. Patrick reached Ireland and the spell was broken.

Ravens are very common in Irish, Gaelic, Norse and possibly all world folklore and are typically associated with war. Irish myth tells of the goddess Morrigan who, having assumed the form of a raven, alighted on Cú Chulainn’s shoulder upon his death.

And last, the salmon straddled by Joyce is the great fish in possession of full knowledge of the world. The salmon was captured by the fearsome warrior Finn MacCool who decided to eat it and thereby gain that world knowledge for himself, but the fishy juices burned his thumb which he promptly stuck in his mouth to relieve the pain, and thus it was that he won the salmon’s insight and wisdom.

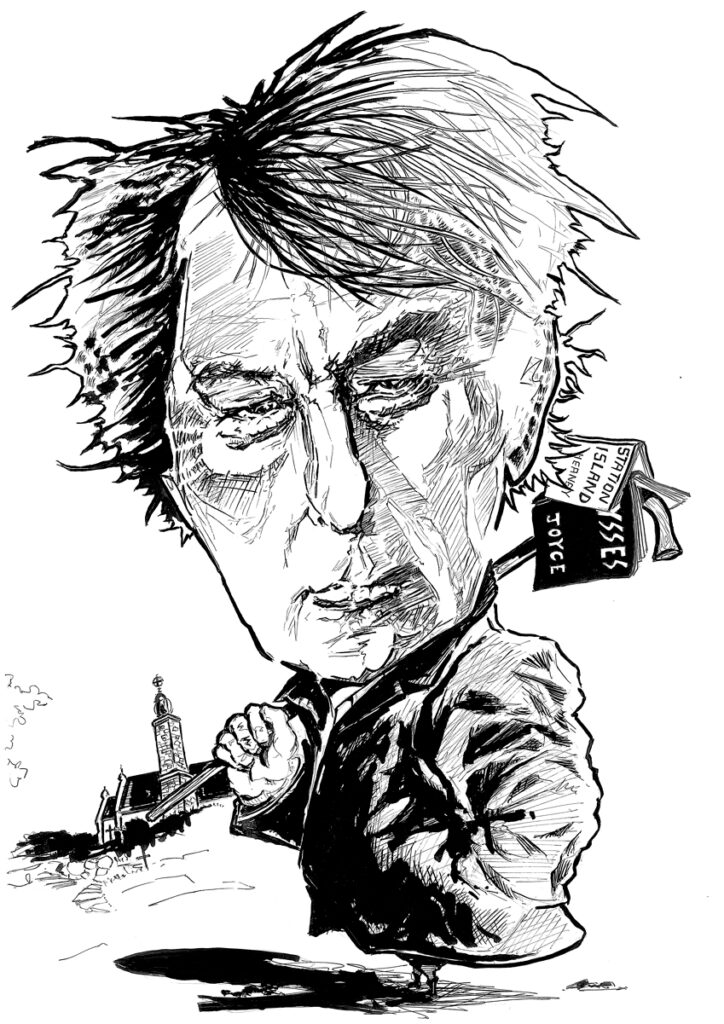

SEAMUS HEANEY

Irish poet, dramatist and translator, Nobel laureate Heaney—here portrayed of indeterminate age in fast-changing light and weather—stands on Station Island in Lough Derg, County Donegal, Ireland. As a young man Heaney made the famous pilgrimage to St Patrick’s Purgatory on the island—twice—and in Section XII of his poetic sequence Station Island, Heaney has a brief encounter with Joyce—or something of a spiritual simulacrum of the great man; perhaps even a sort of extended, somewhat chatty Joycean epiphany in the car park next to the bins (great, honest and direct writing typical of Heaney). Effectively, Joyce tells Heaney just to get the hell on with it—as both man and writer—and have a damn good time doing so too:

for the tall man in step at my side

seemed blind, though he walked straight as a rush

upon his ash plant, his eyes fixed straight ahead.

Then I knew him in the flesh

out there on the tarmac among the cars,

wintered hard and sharp as a blackthorn bush.

His voice eddying with the vowels of all rivers

came back to me, though he did not speak yet,

a voice like a prosecutor’s or a singer’s,

cunning, narcotic, mimic, definite

as a steel nib’s downstroke, quick and clean,

and suddenly he hit a litter basket

with his stick, saying, ‘Your obligation

is not discharged by any common rite.

What you must do must be done on your own

so get back in harness. The main thing is to write

for the joy of it. Cultivate a work-lust

that imagines its haven like your hands at night

dreaming the sun in the sunspot of a breast.

You are fasted now, light-headed, dangerous.

Take off from here. And don’t be so earnest,

let others wear the sackcloth and the ashes.

Let go, let fly, forget.

You’ve listened long enough. Now strike your note.

STEPHEN FRY

Writer, actor, comedian, quiz-master and polymath, a giddily-grinning Fry stands—in every sense—with Joyce (each with his own ashplant). For the website ‘Why I Love This Book’, Fry chose Ulysses as his favourite, which in a short video (still available to view on-line) he describes as a book ‘associated with difficulty whereas in fact it should be associated with joy’. With the possible exception of The Great Gatsby, Fry considers Ulysses ‘the most perfectly written book’. Here, Joyce’s T-shirt bears the word ‘Yes’ in answer to the heartfelt slogan on Fry’s. Molly Bloom’s monologue in the final episode of Ulysses begins and ends with the word; or, as Fry stresses, not one but three yeses, in all their life-affirming (and joyful) glory.

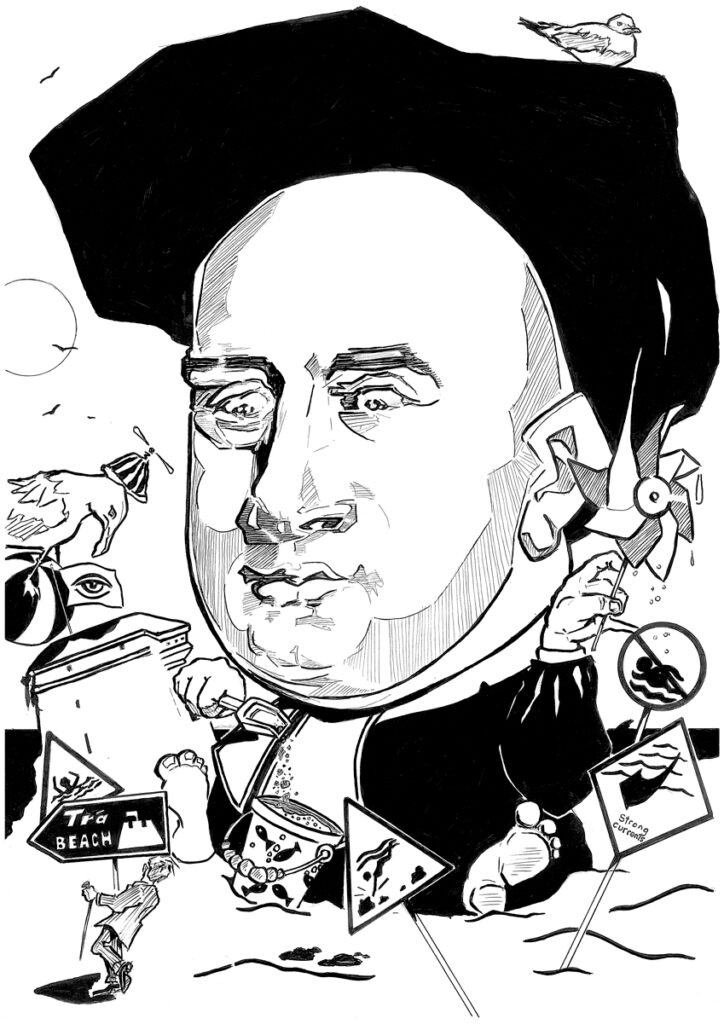

GEORGE BERKELEY

The Irish philosopher, famous for his theories of perception, features fairly prominently in the third (Proteus) episode of Ulysses. Berkeley was a Church of Ireland bishop (Stephen Dedalus refers to him as ‘the good bishop of Cloyne’) and it has often been remarked that Berkeley read the world as a sacred text—although he was hardly alone in this practice as it was not an atypical one for his time, even in religiously ‘skeptical’ intellectual circles.

Stephen’s brooding on Berkeley is well contextualised in the on-line Joyce Project, under the heading ‘Coloured signs’: ‘Berkeley espoused an idealism which needed to respond to the subject-object dualism of Descartes and the empiricism of philosophers like John Locke. For Berkeley, ideal reality had to be defined in terms of the divine being who created them. His response was to argue that the things we perceive cannot be shown to be things at all, but only considerations in the mind of the perceiver. When a human subject thinks that he sees a material object, all that he in fact sees are light and colour… What Berkeley called the “immaterialism” of this view might readily be reconciled with the mystical transcendentalism of a thinker such as Boehme, producing “thought through my eyes.”’

At one point in Proteus, Stephen tells himself to ‘Shut your eyes and see’ so as to experience his surroundings ‘nicely in the dark’. Richard Kearney writes: ‘He hears and feels “his boots crush crackling wrack and shells”. His walking stick (“ash sword”) hangs by his side as he taps away like a blind man along the strand… Opening his eyes again Stephen confirms that the world did not disappear because he stopped seeing it—disproving Berkeley’s idealist thesis that “to be is to be perceived” (esse est percipi). It was “here all the time without you; and ever shall be, world without end”.’ (‘Proteus’ in The Book About Everything—2022, Head of Zeus Ltd.)

This illustration captures a sprightly Joyce as he follows in Stephen’s footsteps, observed by the ever-imposing Berkeley himself (inspired by John Symbert’s portrait of 1727). His senses assailed on all fronts, Joyce closes his eyes and collides with a sign indicating the way to the main beach. Berkeley obliviously carries on playing in the sand, his castle modelled on the Martello tower with which Ulysses opens, slowly sagging into its foundations, thus returning to its original elemental form, never to be seen again in precisely the same configuration.

DEREK WALCOTT

The St Lucian poet and playwright first published his epic poem Omeros in 1990. (Omeros is the Greek name for Homer.) The work reverberates with multiple allusions to Homer’s Iliad, its huge cast of characters (St Lucian fishermen Achille and Hector are major players) as well as the English officer Major Plunkett, his wife Maud, housemaid Helen and not least Walcott himself. The poem is set largely in the 20th century but encompasses many more, seemingly expanding and retracting in time; just as it travels through Lisbon and London, Dublin, Rome and even Toronto. Walcott always happily and gratefully acknowledged his debt to Joyce. In a Paris Review interview he said: ‘When the Irish brothers came to teach at the college in St Lucia, I had been reading a lot of Irish literature: I read Joyce, naturally I knew Yeats, and so on. I’ve always felt some kind of intimacy with the Irish poets because one realised that they were colonials with the same kind of problems that existed in the Caribbean.’

As Ellen Howley writes in The Irish Times (‘How James Joyce’s works informed a generation of Caribbean writers’—5 July 2022): ‘In his poem Volcano, Walcott, who was also a close friend of Irish Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney, writes of the desire to become “the greatest reader in the world” of his literary masters. The poem cements Joyce’s standing in Walcott’s own literary pantheon through the striking opening image: “Joyce was afraid of thunder,/ but lions roared at his funeral.” For Walcott, the Dubliner is not out of place in “this beach house on the cliffs” in “the glow of the volcano” (a reference to St Lucia’s active volcano, Soufrière), his works resonating across the Atlantic in a setting Joyce himself may not even have imagined.’

And as Charles W. Pollard reflects in ‘Traveling with Joyce: Derek Walcott’s Discrepant Cosmopolitan Modernism’ (Twentieth-Century Literature 47.2, Summer 2001, 197): ‘Appropriately… Walcott ends this chapter [5] with a song. He enters a [Dublin] pub, most likely run by one H. C. Earwicker, and discovers that a character from his Omeros, Maud Plunkett, is playing the piano. Among the singers gathered around the piano—the Dead, as Walcott aptly calls them—Walcott sees Joyce for the first time. As his Maud plays the melody,

Mr. Joyce

led us all, as gently as Howth when it drizzles,

his voice like sun-drizzled Howth, its violet lees

of moss at low tide, where a dog barks “Howth! Howth!” at

the shawled waves, and the stone I rubbed in my pocket

from the Martello brought one-eyed Ulysses

to the copper-bright strand, watching the mail-packet

butting past the Head, its wake glittering like keys.

Pollard continues: ‘As Walcott so willingly recognises throughout his career, Mr. Joyce has been one of a few writers in the twentieth century who has led us all. He is a touchstone of our age, and we do well to rub contemporary texts against his work to asses the achievement of subsequent writers. Walcott invites this test, for he trusts that such critical friction will burnish not only Joyce’s work but also his own. He is right.’

Walcott was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1992. In this illustration he stands at the bar in a Dublin pub, pint in hand, with those roaring lions, as Joyce sings—‘his voice like sun-drizzled Howth’—accompanied by Maud on the piano.