Works in Indian ink, Indian ink wash, gouache, marker & pencil

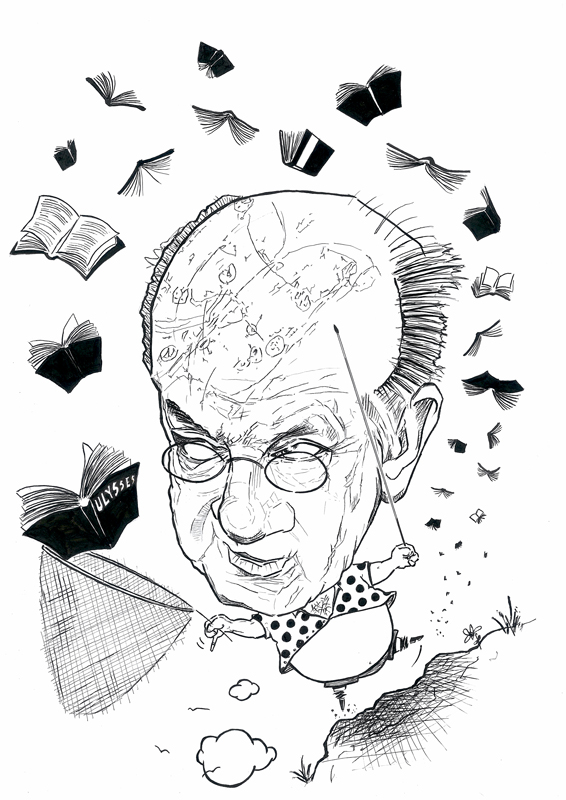

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

In the Scylla and Charybdis episode of Ulysses, Joyce has Stephen expound a somewhat improbable theory about Shakespeare’s Hamlet, which Stephen himself eventually as good as discounts. Those in attendance in the National Library director’s office are John Eglinton, Æ, and Lyster. Stephen’s contention is that Shakespeare associated himself with Hamlet’s father, not Hamlet, as he himself was a cuckold and his wife, Ann Hathaway, far from faithful, strayed with one of Shakespeare’s own brothers.

Joyce doffs his many caps (Bloomian bowlers) to one he knows he owes

so much.

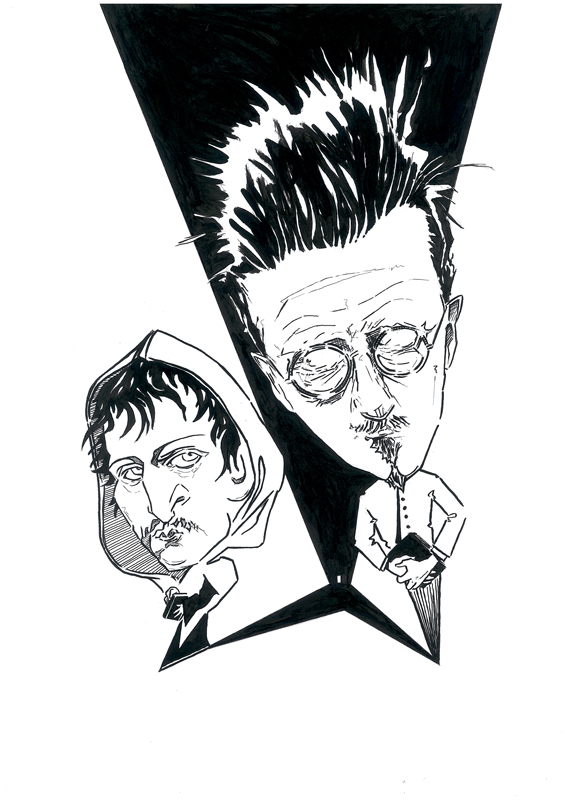

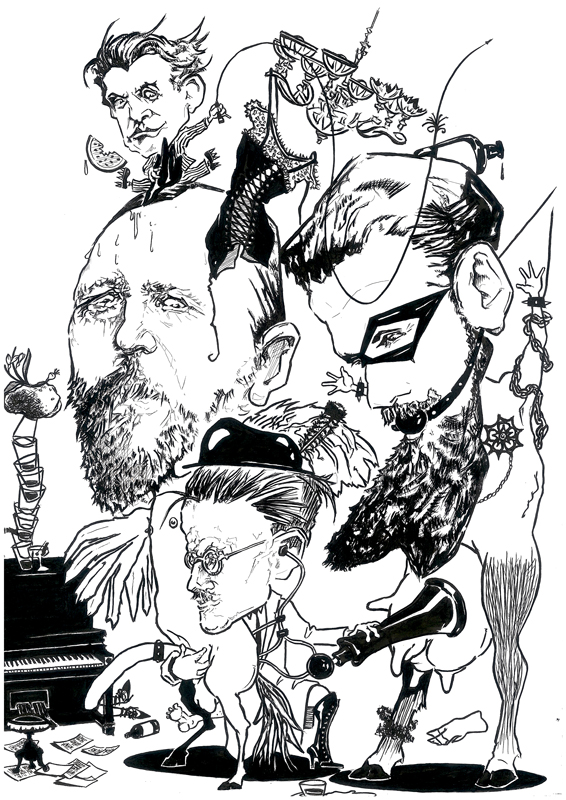

ARTHUR SYMONS & THE SYMBOLIST POETS

Poet and critic, a prolific writer on the literary trends of his time, Symons is best remembered today for his 1899 extended essay, The Symbolist Movement in Literature. Here he ponders his subjects–clockwise from top left: Arthur Rimbaud, Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine, Gérard de Nerval (with his pet lobster which he would take for walks in Paris), Joris-Karl Huysmans, and Stéphane Mallarmé in the centre.

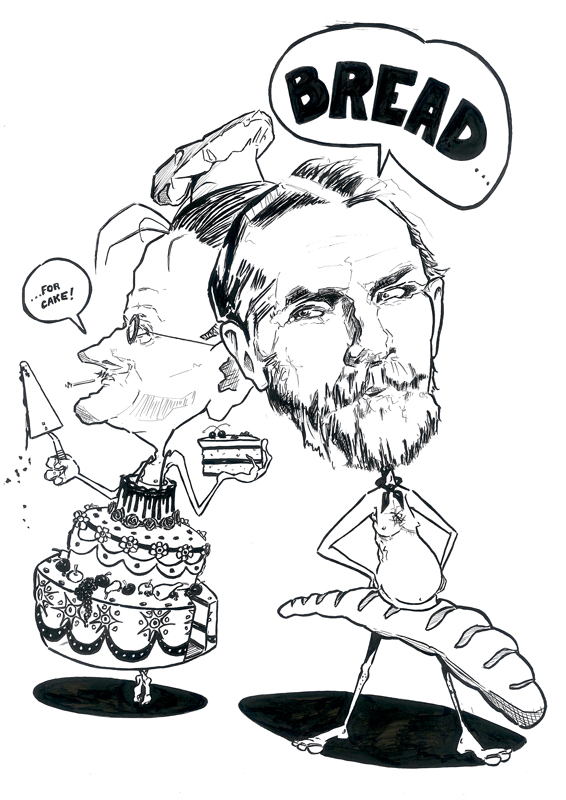

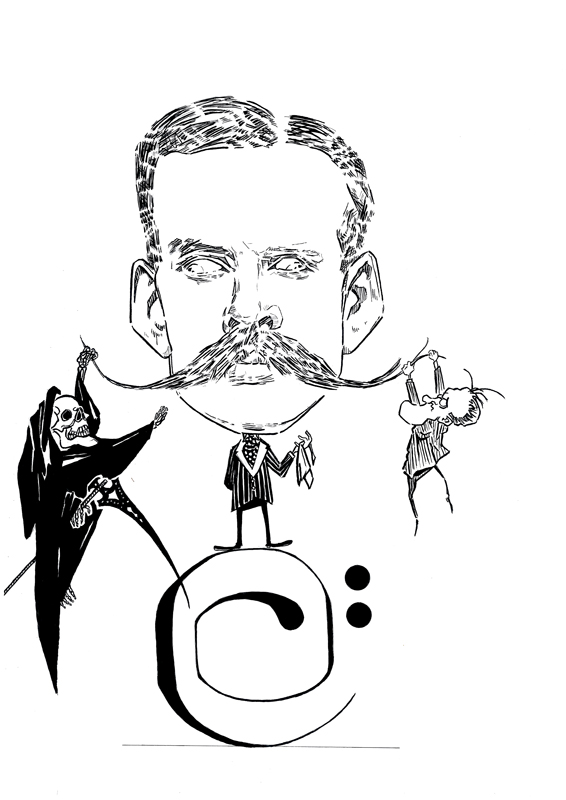

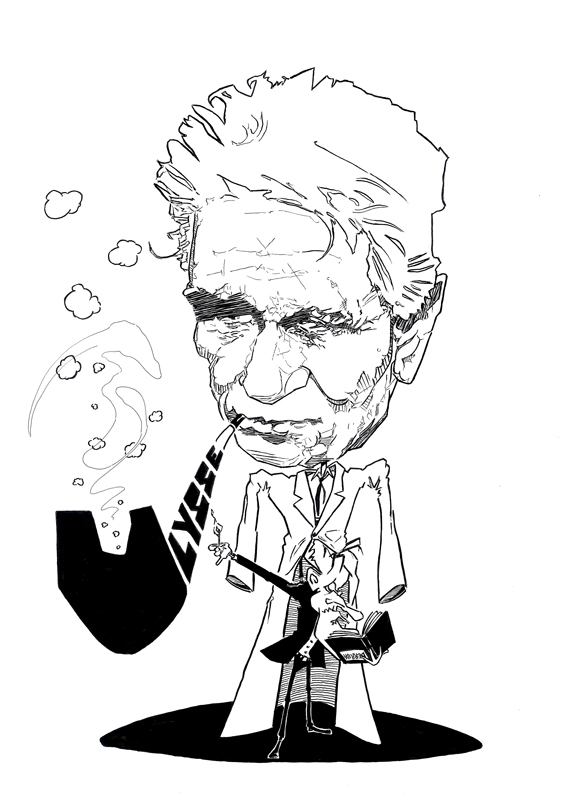

ÉDOUARD DUJARDIN

Dujardin is considered one of the founders of the stream of consciousness technique in his novel, Les lauriers sont coupés and, as such, an influence on Joyce’s employment of a similar technique in Ulysses. Joyce was generally dismissive of Dujardin, regarding him as a very minor writer. When asked about Dujardin’s influence on his own work, Joyce famously replied: ‘Bread, for cake’.

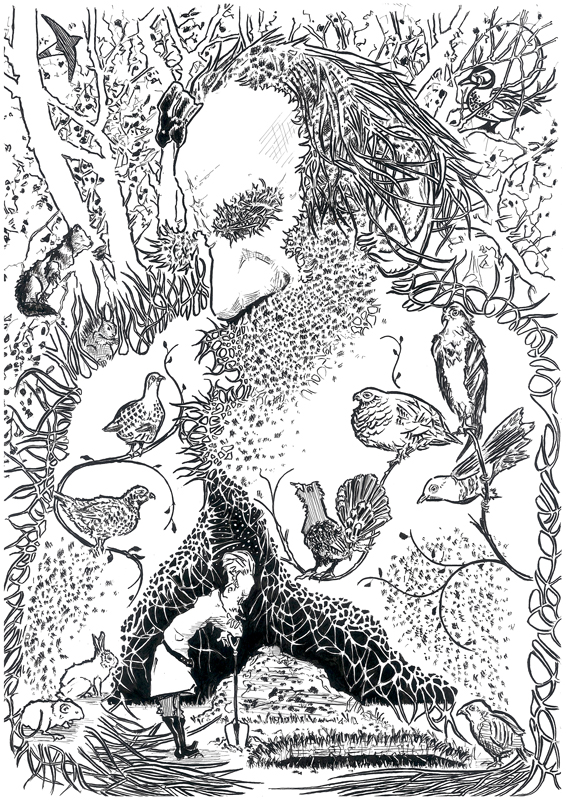

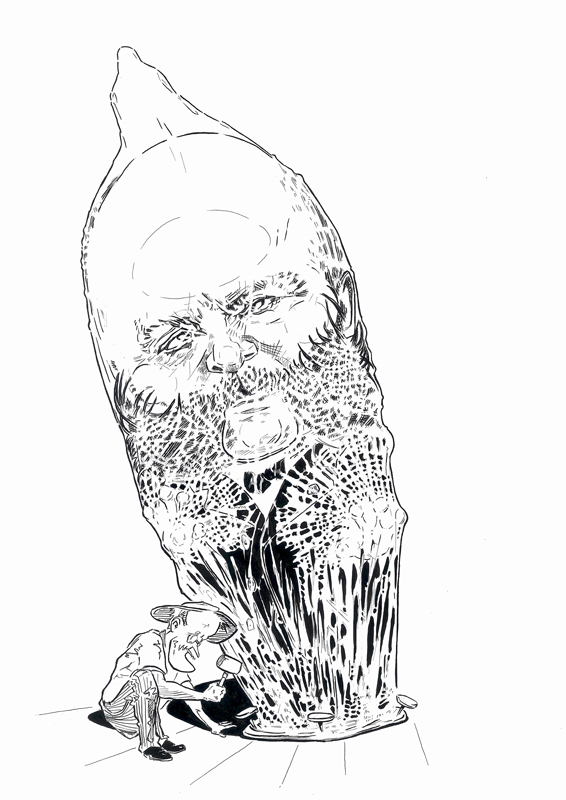

LEO TOLSTOY

In his September 18, 1905 letter to his brother Stanislaus–who had recently offered very high praise of some of his stories that would eventually be published under the title Dubliners–Joyce replied a little cantankerously with regards Tolstoy: ‘As for Tolstoy I disagree with you altogether. Tolstoy is a magnificent writer. He is never dull, never stupid, never tired, never pedantic, never theatrical! He is head and shoulders over the others.’ And some years later he would advise his step-grandson to read, among others, Tolstoy’s 1886 short story ‘How Much Land Does a Man Need?’ which Joyce considered a masterpiece excelling all others; it concerns the peasant Pakhom who stops at nothing to sate his voracious appetite for more and more land until he drops dead and is buried by his servant in a six foot long grave–in other words, all the land a man needs.

Tolstoy is portrayed at the end of his life, with his prophet’s beard, a man very much of the land. Joyce contemplates the grave he has just dug. The various fauna are native to or common in Russia and serve as emblems and so are not drawn to scale.

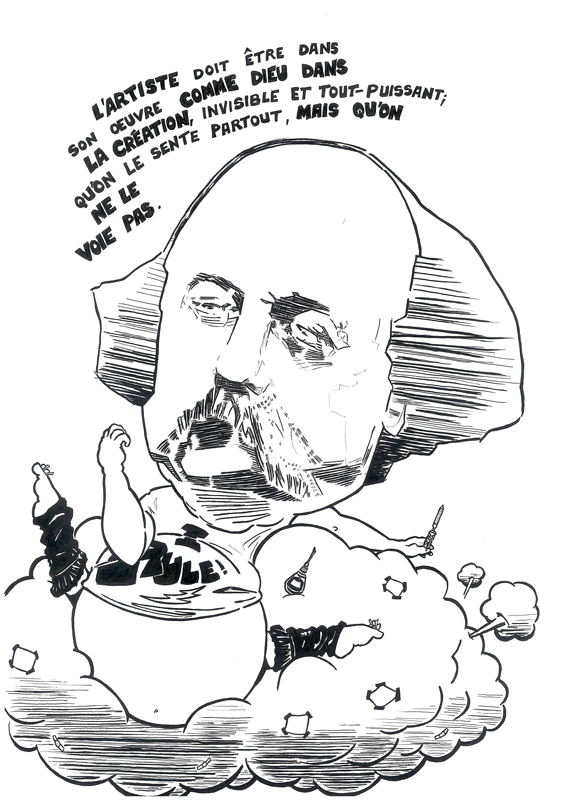

GUSTAVE FLAUBERT

In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Stephen Dedalus–after dwelling on the differences between the three modes of writing (the lyrical, the epical and the dramatic)–insists that: ‘The artist, like the God of the creation, remains within or behind or beyond or above his handiwork, invisible, refined out of existence, indifferent, paring his fingernails.’ Which is a rough translation of the text in this illustration. (Flaubert said nothing of ‘paring his fingernails’.)

Flaubert’s words are taken from his letter of 18 March 1857 to Mlle. Leroyer de Chantepie, who had expressed her unbridled admiration for his novel Madame Bovary and her conviction that much of its value resided in its author’s personal sentiments and principles to be found therein. Flaubert politely but stridently refuted this notion: ‘Madame Bovary n’a rien de vrai. C’est une histoire totalement inventée; je n’y rien mis ni de mes sentiments ni de mon existence. L’illusion (s’il y en a une) vient au contraire de l’impersonnalité de l’oeuvre. C’est un de mes principes, qu’il ne faut pas s’écrire.’ (There is nothing true in Madame Bovary. The tale is totally invented; I have put nothing of my own feelings or life into it. On the contrary, its illusion [if there is one] arises from the impersonality of the work. That is one of my principles, that one must not write oneself.)

The notion that Stephen’s view was and forever remained Joyce’s view and was one that he deliberately applied throughout the writing of both Ulysses and Finnegans Wake persists to this day. Richard Ellmann: ‘The theory of art and its practice which is usually drawn from his writings is that the artist is too Godlike to take sides for or against his characters. Joyce, it is said, offers instead multiple perspectives on the action, in the form of different styles and different narrators, without choosing among them. This is to malign God as well as Joyce. The view has caught on a little because Flaubert sometimes expressed it, and Joyce is held to be another Mauberley having Flaubert for his true Penelope. Yet Flaubert’s explicit statements about artistic detachment are inadequate to explain Madame Bovary, where the author, however unconfiding, describes the feelings of his characters with an attentiveness that may be pokerfaced but is not heartless.’ (The Consciousness of Joyce.)

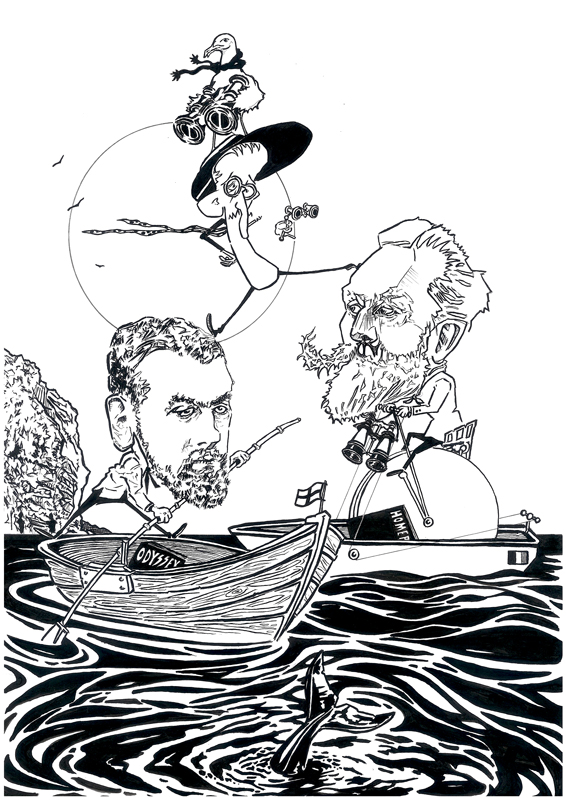

SAMUEL BUTLER & VICTOR BÉRARD

Butler wrote at least two speculative studies of Homer’s ‘true’ heritage (not uncommon in Victorian times, given the rise of archaeology and anthropology): in one he alleged that Homer had not even been male but, rather, a Sicilian woman, and that Ulysses’s voyages all occurred in or around Trapani. For his part, the French politician and scholar Bérard surmised that The Odyssey had its true origins–not least linguistic–in Phoenicia as opposed to Greece. His Homer was a Greek but a very worldly Greek, steeped in the language and lore of cultures far beyond his native land.

And so the two scholars blithely float off in different directions on a cloudless Mediterranean. Joyce, with his opera glasses (and accompanied by an Irish seagull overdressed for the part), also considers other viewpoints–all of which end up, one way or another, in Ulysses.

GIORDANO BRUNO

One of Joyce’s biggest intellectual heroes, Bruno was burned at the stake in Florence for heresy (centuries later pardoned by a rightly-ashamed Catholic Church). Most of his very free-thinking challenged Catholic dogma & doctrine, a stance with which Joyce easily identified.

Richard Ellmann: ‘But for the principal context of the first six chapters [of Ulysses], Joyce depended upon the man whom he valued as “the father of what is called modern philosophy”. He awarded this title, in a review in 1903, to Giordano Bruno. Bruno more than anyone probably enlarged Joyce’s perspective beyond Aristotle. …Joyce did not respond to the Hermetic side of Bruno …but he respected his unAristotelian passion, his “ardent sympathy with nature as it is–natura naturata”, his mystical faith in interconnection as a world-principle.’ (Ulysses on the Liffey.)

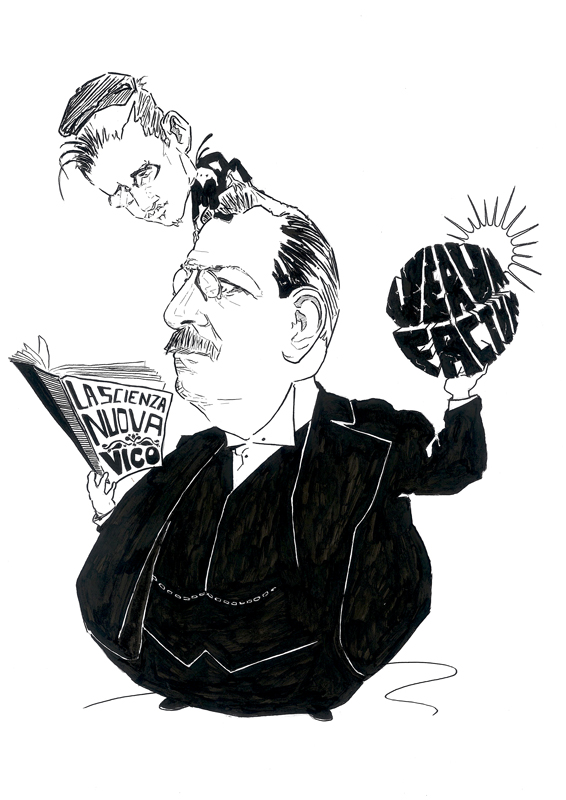

BENEDETTO CROCE (& GIAMBATTISTA VICO)

In James Joyce, Richard Ellmann writes: ‘Joyce also knew Croce’s Estetica, with its chapter on Vico. Croce’s restatement of Vico, “Man creates the human world, creates it by transforming himself into the facts of society: by thinking it he re-creates his own creations, traverses over again the paths he has already traversed, reconstructs the whole ideally, and thus knows it with full and true knowledge,” is echoed in Stephen’s remark in Ulysses (505 [623]), “What went forth to the ends of the world to traverse not itself. God, the sun, Shakespeare, a commercial traveller, having itself traversed in reality itself, becomes that self. …Self which it itself was ineluctably preconditioned to become. Ecco!”’

Croce holds in one hand a copy of Vico’s magnum opus Scienza Nuova, or New Science (1725), which a young Joyce peruses from Croce’s head. In his other hand Croce holds a truncated form in stone of Vico’s most famous aphorism: Verum esse ipsum factum (‘Truth is itself something made’).

ELEANORA DUSE (LA DUSE)

Joyce was a huge fan of the Italian actor, whom he had seen in D’Annunzio’s plays (he sent her an admiring letter to which she never replied and he kept a photograph of her on his desk). Born in 1858, La Duse–as she was affectionately known–had an affair with Verdi’s librettist, Arrigo Boito, and, after that ended, began another with D’Annunzio, who wrote four plays for her. Joyce first saw her in London in 1900. He and his father attended performances of La Gioconda and La Città Morta by D’Annunzio at the Lyceum Theatre. She was also considered one of the leading Ibsen actresses of the time and Joyce leapt at the chance to see her perform in a production of Ibsen’s Rosmersholm in February 1905 at the Teatro Verdi, but was disappointed by both the play and her performance.

Joyce’s devotion to La Duse never faded and Ellmann suggests that at one time Joyce may have wanted to succeed D’Annunzio in her affections.

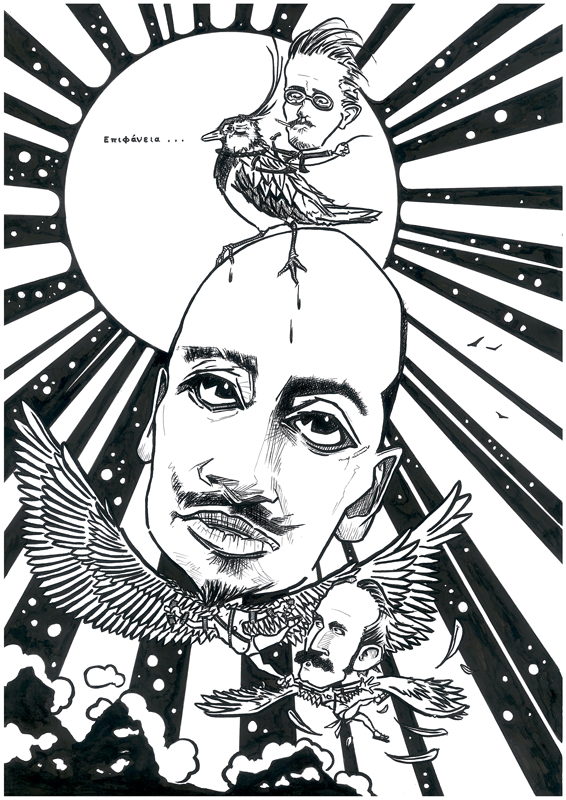

GABRIELE D’ANNUNZIO & WALTER PATER

Poet, novelist and later fascist (his writing and speechifying style was an influence on Mussolini), the somewhat half-baked D’Annunzio’s early novels attracted Joyce for their ideas on ‘epiphany’–so central to an understanding of Joyce’s early aesthetic theories as developed in Portrait of the Artist and to a lesser extent Ulysses. Here, D’Annunzio as Daedalus and the Victorian writer Walter Pater as Icarus (Pater also wrote on the nature of epiphany) fly towards the sun; above them Joyce reins in a lapwing–briefly a symbol of memory and the creative process for Stephen Dedalus. The Greek word here is ‘Epiphany’.

Justin Beplate: ‘Stephen’s arcane, eclectic learning may well endow him with a certain intellectual leverage in his ongoing jousts with Mulligan and his court of jokers; yet it also masks a deeper sense of anxiety over the uses and abuses of memory in mounting sustained flights of creative daring. His musings on his own uncertain destiny in the Library scene of Ulysses, for example, betray his doubt in stark terms: “Fabulous artificer. The hawklike man. You flew. Whereto? Newhaven-Dieppe, steerage passenger. Paris and back. Lapwing. Icarus.” The juxtaposition of lapwing and Icarus alludes to the twin dangers attending Stephen’s artistic ambition: …below, the shallow skimmings of a memory-bound imagination; above, the catastrophe of an unfettered creative drive–unfettered, that is, by the various modes of remembering that shape Stephen’s aesthetic ambitions.’ (Études Anglaises 2007/1–Vol. 60.)

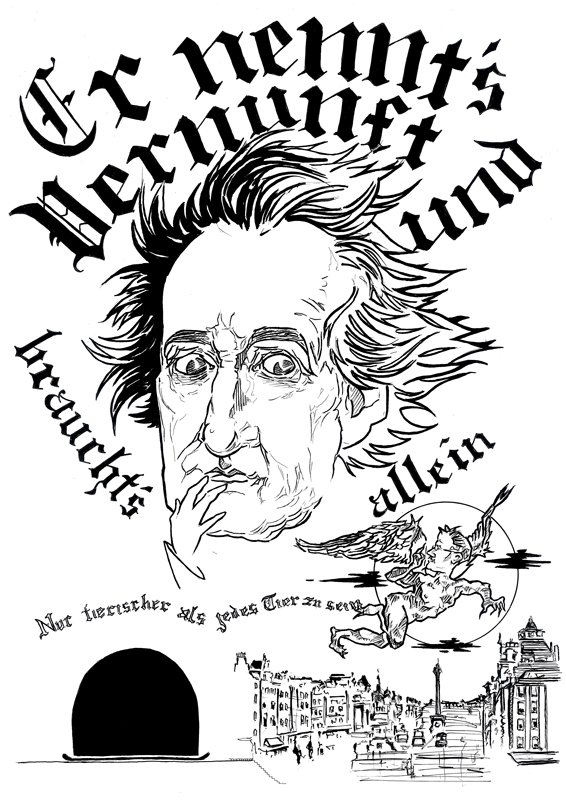

Johann Wolfgang von GOETHE

The German writer’s Faust greatly influenced Joyce, particularly the Circe episode in Ulysses. Joyce as Mephistopheles is copied from the famous lithograph by Delacroix of the demon flying over Wittenberg. (Joyce’s flightplan takes him over Dublin instead.)

The German words in this drawing are uttered by Mephistopheles in the ‘Prologue in Heaven’ from Goethe’s Faust: ‘He calls it reason/But its only use/Is to find out how/To be a perfect beast.’ (John Armstrong translator.)

Bloom’s bowler looms large on the horizon.

RICHARD VON KRAFFT-EBING, HAVELOCK ELLIS

(& LEOPOLD VON SACHER-MASOCH)

In a tribute to the Circe episode and the many transformations therein, the Austrian writer Leopold von Sacher-Masoch whips up a sexual storm on the head of the partially metamorphosed German psychiatrist–and expert on ‘deviance’–Richard von Krafft-Ebing, as his British counterpart Havelock Ellis is forced to watch. Joyce was familiar with the work of all three men, including Krafft-Ebing’s 1886 Psychopathia Sexualis (the most risqué sections of which are written in Latin to fend off those without medical training); and Studies in the Psychology of Sex (1897-1928) by Ellis, particularly Volume 5 in which the taboo subject of human attraction to animals is considered (among much else). Other pointers in this drawing to the Circe episode include the smashed chandelier; the moorcock’s feather in Joyce the doctor/veterinarian’s Bloomish bowler; and Bloom’s lucky potato and his sprig of moly.

Joyce wields a Victorian stethoscope as he examines the ‘animals’ in his care.

HARRY PLUNKET GREENE

At one of his concerts, the famous Irish baritone impressed Stanislaus Joyce, who in turn impressed his brother James in a letter recounting his impressions. In James Joyce, Richard Ellmann follows the trail. Plunket Greene’s concert included ‘one of Thomas Moore’s Irish Melodies called “O, Ye Dead!”. The song, a dialogue of living and dead, was eerie enough, but what impressed Stanislaus was that Greene rendered the second stanza, in which the dead answer the living, as if they were whimpering for the bodied existence they could no longer enjoy … James was interested and asked Stanislaus to send the words, which he learned to sing himself. His feelings about his wife’s dead lover found a dramatic counterpart in the jealousy of the dead for the living in Moore’s song … Another aspect of the rivalry is suggested in Ulysses, where Stephen cries out to his mother’s ghost, whose “glazing eyes, staring out of death, to shake and bend my soul, …to strike me down,” he cannot put out of mind: “No, mother. Let me be and let me live.” That the dead do not stay buried is, in fact, a theme of Joyce from the beginning to the end of his work.’

Greene stands on an old style bass clef, not uncommon in the sheet music of the time. Joyce’s hanging pose is copied after Harold Lloyd’s iconic image from the 1923 film classic Safety Last!

DJUNA BARNES

The American writer, journalist and artist, famed for her novel Nightwood, was a huge admirer of Joyce. This portrait of Joyce is inspired by Barnes’s own sketch of him.

GEORGE RUSSELL ‘Æ’

Editor, writer, poet, painter and fervent Irish nationalist, George Russell–also known under the pseudonym Æ (from Greek ‘Aeon’)–was often the butt of Joyce’s affectionate humour towards him. As a character in the Scylla and Charybdis episode of Ulysses he shows little regard for Stephen’s theory on Shakespeare’s Hamlet. After borrowing money from Russell, Stephen remarks: ‘A.E.I.O.U.’ knowing full-well he’s unlikely ever to pay him back. Following the publication of his first book of poetry, Russell met Joyce in 1902 through what was known as the Irish Literary Revival.

He was a mad cyclist, often seen clipping at speed through the streets of Dublin. He was also a mystic and theosophist and wrote on both economics and politics. In 1897 he joined the Irish Agricultural Organization Society (IAOS), overseeing the establishment of co-operative banks in overpopulated districts of the west of Ireland. Over time he became one of the leading figures of the Co-operative movement and his fame spread throughout Ireland.

Madame Blavatsky, the Russian co-founder of the Theosophical Society, rides Russell’s rump as he tries to elude the two-headed octopus (which he mystically ponders in Scylla and Charybdis): ‘…one of whose heads is the head upon which the ends of the world have forgotten to come while the other speaks with a Scotch accent’–in another fond ribbing from Joyce, who in this picture wields the Dedalian ashplant to bring the mystic Æ crashing down with Aristotelian firm fact and force.

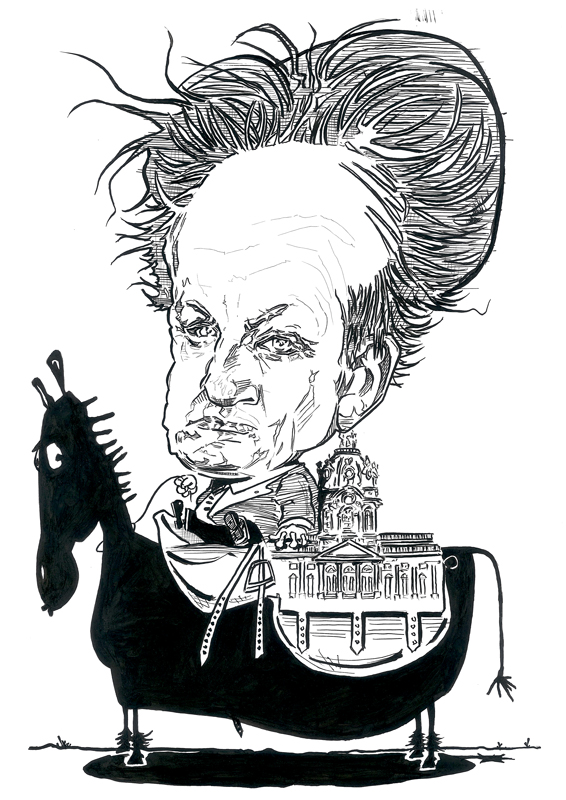

GERHART HAUPTMANN

In 1901 Joyce translated two of the German dramatist Hauptmann’s plays: Vor Sonnenaufgang (Before Sunrise) and Michael Kramer. Apart from wanting to challenge and improve his German, he was keen to persuade the Irish Literary Theatre to stage them. All his life, Joyce admired what he considered to be Hauptmann’s integrity and empathy for the common man and woman. In a letter to Stanislaus he wrote: ‘I have found nothing of the charlatan in him yet.’

Hauptmann sits on a draft horse, key symbol of the Working Man he so ardently championed in his work. The horse’s saddle is modelled on Charlottenburg Palace in Berlin, where Hauptmann’s literary career began in earnest in 1889 (he joined ‘Durch’, the naturalist literary association, in the same year). Hauptmann’s reputation has not held up well–his work started to fall out of fashion well before his death and his uncritical association with the Nazi regime further dented his stature after the war.

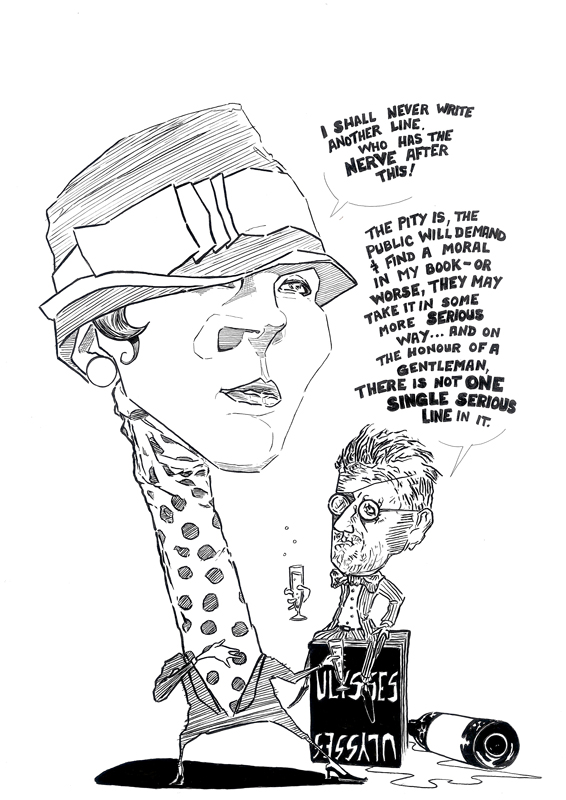

ANTHONY COMSTOCK

One legal and ‘moral’ thorn in the sides of anyone affiliated with Modernism, the bufoonish Comstock was a United States Postal Inspector and secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV). As Kevin Birmingham writes in The Most Dangerous Book: ‘Comstock saw human nature as a withering thing, a form of purity corrupted by the fallen world. His mechanism for rolling back the tide of lust was the United States Post Office. …The 1873 Comstock Act made the distribution or advertisement of any “obscene, lewd, or lascivious book, pamphlet, picture, paper, print or other publication of an indecent character” through the U.S. mail punishable by up to ten years in prison and a ten-thousand-dollar fine.” Comstock destroyed books by the ton and imprisoned thousands of pornographers. …Pound was still railing against the Comstock Act in the late 1920s, when he wrote to the Supreme Court Chief Justice Taft to ask for help overturning a stature enacted, he insisted, by “an assembly of baboons and imbeciles.” Part of what made the Comstock Act so loathsome was that it underscored the fact that renegades and iconoclasts like Pound depended on the Post Office for their survival.’

The Act also made it illegal for the U.S. Post Office to deliver any published material or practical methods relating to contraception, including condoms. In this illustration: ever the intrepid literary explorer, James Joyce deals quickly and effectively to neutralise this moronic threat to his livelihood.

MARGARET C. ANDERSON

Founder, editor and publisher of the Chicago monthly literary magazine The Little Review, which published in serial form several episodes of Ulysses, Anderson was a complete and formidable ‘one-off’, even for the times. Other contributors to her magazine included Eliot, Barnes, Hemingway, Sherwood Anderson and Marianne Moore. It also carried, in reproduction, artwork by Picabia, Brancusi and Cocteau. Anderson was the first woman to speak out publicly in print on the issue of gay rights (she and Jane Heap would become lovers), and her association with and support for the anarchist Emma Goldman brought her no end of trouble.

At one point she was so hard up that she was forced to camp on the shores of Lake Michigan with her two sisters: ‘The tents had wooden floors and oriental rugs. They roasted corn by the fire, baked potatoes in the ashes and washed their dishes and clothes with sand. …Friends visited over the next six months. The writer Sherwood Anderson told stories by the campfire, and other writers pinned poems to the tents like valentines.’ (Kevin Birmingham, The Most Dangerous Book.)

In this picture, Margaret is joined around the campfire by Emma Goldman and Sherwood Anderson, toasting marshmallows.

DORA MARSDEN (& MAX STIRNER)

Suffragette and founder and editor of the literary magazine The Egoist (formerly The New Freewoman) which published work by, among others, Joyce and Eliot, Marsden was greatly influenced by the 1844 treatise The Ego and His Own, in which the German philosopher Max Stirner maintained ‘that the individual was the only source of virtue and the only reality–everything else was an abstraction, and all abstractions were “spooks,” ghosts vexing the ego. Anti-individual forces–corporations, bureaucracies, churches, states–were not merely unjust. They were unreal. Such sweeping skepticism generated sweeping dismissals of higher causes and concepts like God, truth and freedom. …It inspired her [Marsden’s] choice to rechristen The New Freewoman as The Egoist. Shrinking the world down to the ego made the twentieth century manageable. It fuelled [Emma] Goldman’s optimism and Joyce’s dogged determination.’ (Kevin Birmingham, The Most Dangerous Book.)

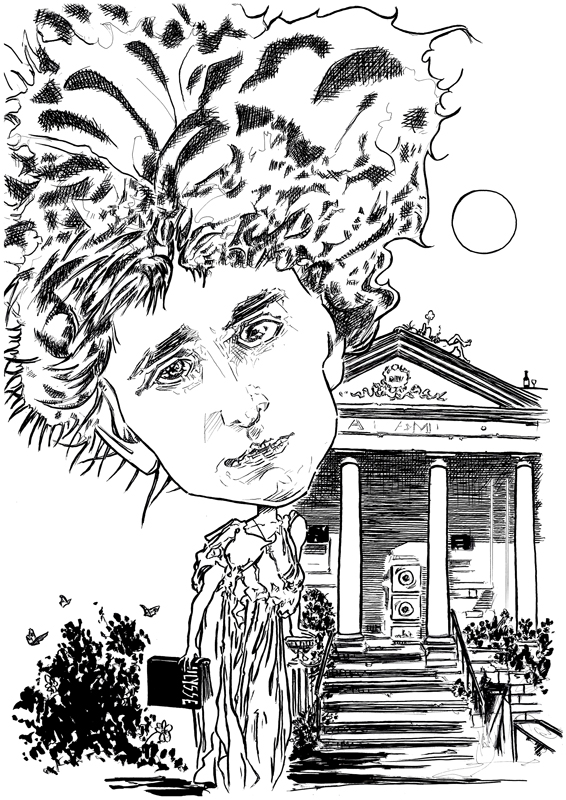

NATALIE BARNEY

Barney was a socialite and literary hostess based in Paris and although Joyce was little impressed when he attended one of her salons, she is included here because she embodies the times so well and, by all accounts, was an all-round ‘good egg’ who knew just about everyone worth knowing. The classical temple behind her was a famous feature of her hidden garden in Paris.

Barney is dressed in a copy of a Hellenistic costume as sketched by Lord Leighton of one of his life models. Joyce sunbathes on the roof.

PAUL LÉON

Joyce’s close friend, Léon was a Russian-born Jew, a lawyer and a lover of art and literature. Following Joyce’s death, he returned to Joyce’s rue des Vignes apartment in Paris just after the start of the Nazi Occupation and devoted himself to sorting out Joyce’s books and personal papers, despite the grave risk to himself. When Samuel Beckett–on his way out of Paris–ran into Léon, he was shocked to find him still there. Léon got Joyce’s effects to the Irish Ambassador to occupied France, with (writes Ellmann): ‘…instructions that they should be turned over to the National Library of Ireland, there to be kept sealed for fifty years. Léon lived furtively in Paris into 1941. One day Samuel Beckett saw him and said in alarm, “You must leave at once.” “I have to wait till tomorrow when my son takes his bachot,” said Léon, as good a father as Joyce.’ (Ellmann, James Joyce.)

He was arrested by the Nazis the next day. Léon passed seven months in France’s transit camps at Drancy, then at Compiègne, after which he was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau on 27 March 1942 and there murdered. A great man, Joyceans worldwide owe him an eternal debt of gratitude.

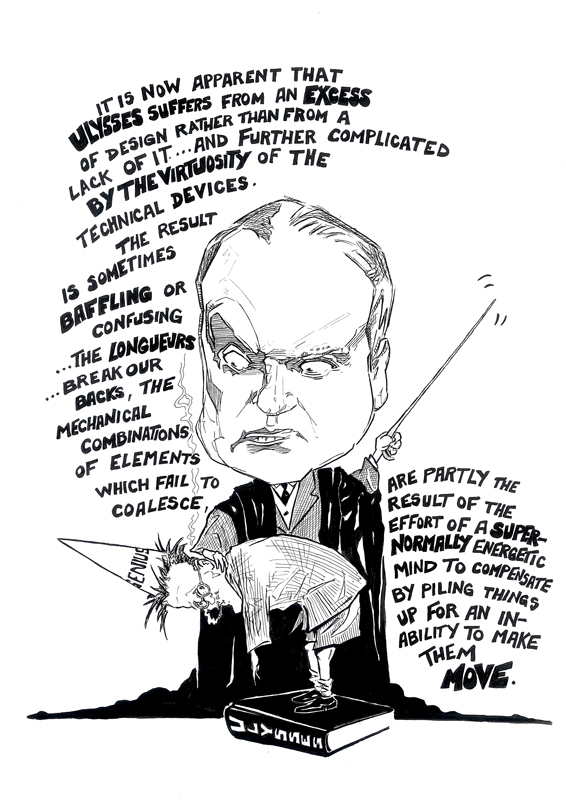

EDMUND WILSON

Wilson’s words are lifted from his 1931 classic Axel’s Castle, one of the first serious critical considerations of Joyce (and Eliot et al in light of the Symbolists’ influence). Wilson’s book provided context and support for Joyce, and yet, Wilson has always read to me like a jealous, truculent Victorian headmaster who spectacularly misses the point at times and cannot resist administering a damn good thrashing (in this image–heavy with irony–by utilising Stephen Dedalus’s ashplant).

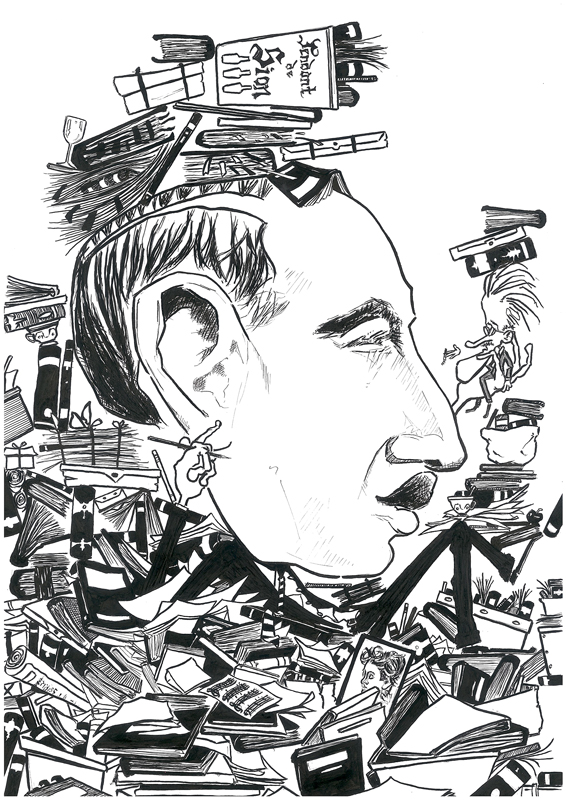

VLADIMIR NABOKOV

Nabokov considered Ulysses THE great literary masterpiece of the 20th century and included it in his lectures on literature at Cornell. For the benefit of his students, he famously sketched a map of Dublin as traversed by Leopold Bloom, which here appears on his brow. A devout lepidopterist, Nabokov lectures whilst chasing after the brilliant and ever-elusive specimen Ulysses.

JACQUES DERRIDA

In his 2020 biography of Derrida, An Event, Perhaps (Verso), Peter Salmon writes: ‘Ulysses and Finnegans Wake swiftly became crucial books for Derrida. They were examples of the sort of meta-discursive texts which his own work set out not only to deconstruct, but to generate and emulate–“the potential memory of mankind”. This “most Hegelian of modern novelists”, as he put it at the end of his 1964 essay Violence and Metaphysics, had “read all of us–and plundered us”.’

From Derrida’s pipe rises a trail of smoke in the form of Thoth–body of a man with the head of an ibis–the ancient Egyptian god of writing. In his book Dissemination (1972), Derrida considers Thoth’s divine attribute as explored by Plato in the Phaedrus, in which he sets out his view of writing as a pharmakon, which can mean both poison and remedy. The point, of which Derrida makes much (and then much more), is that these apparently contradictory definitions are complementary and symbiotic. Writing is unruly, ungovernable …an ever-expanding, infinite network of associations and correspondences in which truth is impossible to pin down; hence Plato’s disdain for writing and Derrida’s and Joyce’s elective affinity for it, and for each other–both disposed to push language to its limits.

And so Derrida stands on the broad shoulders of Joyce who lights the Ulysses pipe on which Derrida vigorously–and so indebtedly–puffs away.

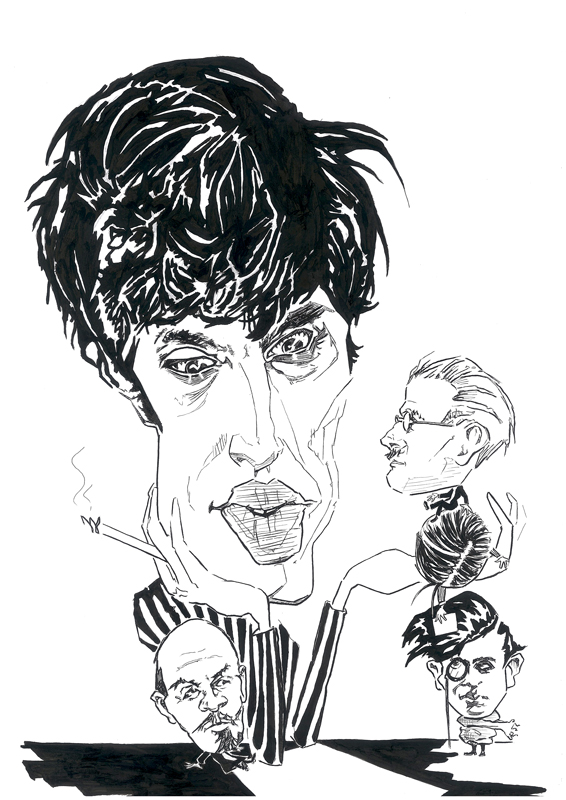

DAVID FOSTER WALLACE

Wallace poses with some of the writers and thinkers who influenced him the most–trapped in his sweat-soaked bandana which became his sartorial trademark. From left to right: Franz Kafka (under his bowler); Thomas Pynchon; Stephen King; Donald Barthelme (barely visible below King); Don DeLillo; G.H. Hardy; David Markson; and finally–beating them all–Joyce, who catches the tennis ball in his wine glass. Wallace was an excellent tennis player in his youth and the game features strongly in his cult classic Infinite Jest.

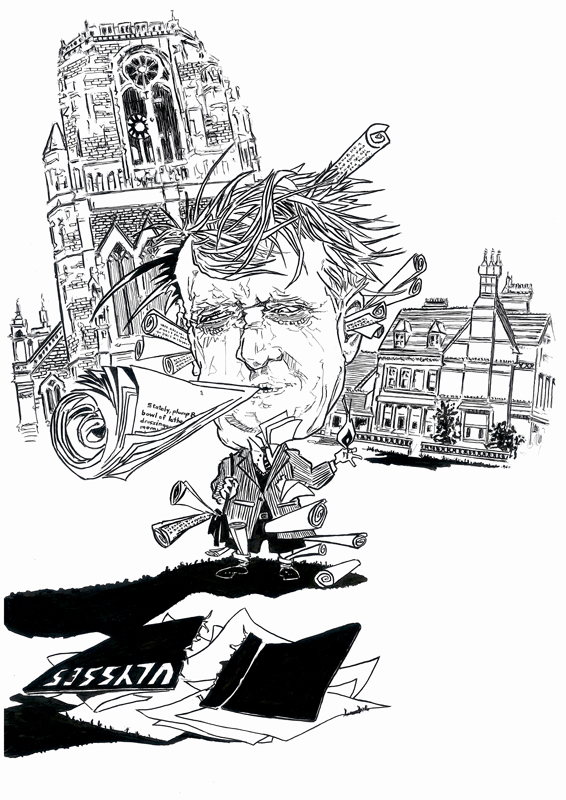

ANTHONY BURGESS

For his entire career Burgess was near-obsessed with Joyce. His two most famous novels–A Clockwork Orange and Earthly Powers–are, in very different ways, very Joycean. There are several contradictory accounts of how Burgess first came to own a copy of Ulysses, not least from Burgess himself. In his critical book on Joyce, Here Comes Everybody, written for the common reader, Burgess claimed that ‘(As a schoolboy I sneaked the two-volume Odyssey Press edition into England, cut up into sections and distributed all over my body.)’

In The Real Life of Anthony Burgess, Andrew Biswell reflects in some detail on Burgess’s encounters with the clerical and secular authorities when, as an intellectually rambunctious young man under the influence of Joyce, he questioned the foundations of their power, particularly at the Church of the Holy Name of Jesus on Oxford Road in Manchester (which looms large over Burgess the ‘lad’ here on the left) and when he was in the sixth form at Xaverian (pictured right). In this illustration, ‘bad boy Tony’ in his school uniform (perhaps fresh from a theological dispute with a Jesuit priest), prepares to smoke a joint rolled from the first chapter of Ulysses–giving him a high from which he would never really come down.

TOM STOPPARD

A young Stoppard ruminates over what will become his next hit play, Travesties, which is based on an awkward and litigious encounter between Joyce and one Henry Carr. It is a fact that Joyce, Lenin and Tristan Tzara were all living in Zurich in 1916–a fact with which Stoppard takes huge liberties and has great fun. As Hermione Lee writes, echoing Stoppard: ‘The play is a travesty of history, and all the historical characters are travesties, or caricatures, of their real, historical selves. Its plot is a travesty of Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest. Henry Carr, in the play, says venomously that his legal battle with Joyce was “a travesty of justice.” And each character thinks the other’s view of art is a travesty of the truth.’ (Tom Stoppard, A Life.)

In this drawing, the now largely-forgotten Carr–upon whom Joyce sits and would soon revenge himself in the Circe episode of Ulysses–hands a ‘directorial note’ of sorts to Tristran Tzara as Lenin looks on and Joyce pleads his case with Stoppard.

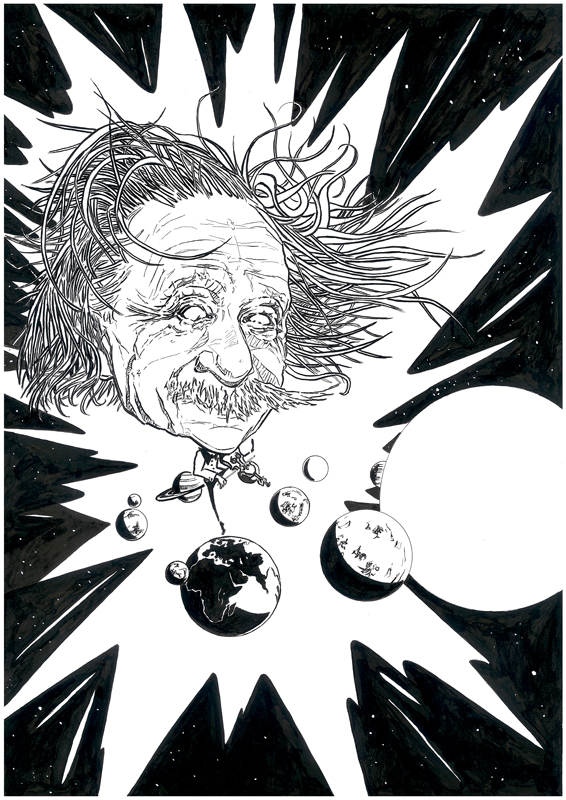

ALBERT EINSTEIN

Joyce and Einstein also never met but the former was certainly familiar with the latter’s work and ideas. At his talk to promote the imminent publication of Ulysses, Valery Larbaud insisted that literary circles were as well acquainted with Joyce’s name as scientific circles were with Freud’s or Einstein’s. Joyce played ingeniously with ideas of space and time in both Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. As Ellmann points out, in Ulysses ‘Space [in the first chapter] had offered extension, time [in the second chapter] …offers succession.’ (Ulysses on the Liffey.)

Elsewhere he adds: ‘Joyce found in space and time powers as elemental as Neptune and Hyperion, but secularised. Our lives are on the one hand enforced movements from room to room, concessions to our surroundings. On the other hand, our lives are enforced surrenders to tick and tock, temporal exigencies which wear us down whether we like it or not. We are creatures of our maps, and of our watches. When T. S. Eliot writes, “Teach us to sit still”, or speaks of “the still point of the turning world”, he seeks freedom from these mundane powers. But where Eliot looks for a relief which is institutionally covenanted, Joyce finds a possibility of relief in secular terms. We free ourselves from time and space, from history and geography, by memory, which fables itself into art.’ (The Consciousness of Joyce.)

Einstein adored playing the violin, particularly Mozart’s sonatas written for the instrument. In this drawing he plays on a diminutive Joyce.